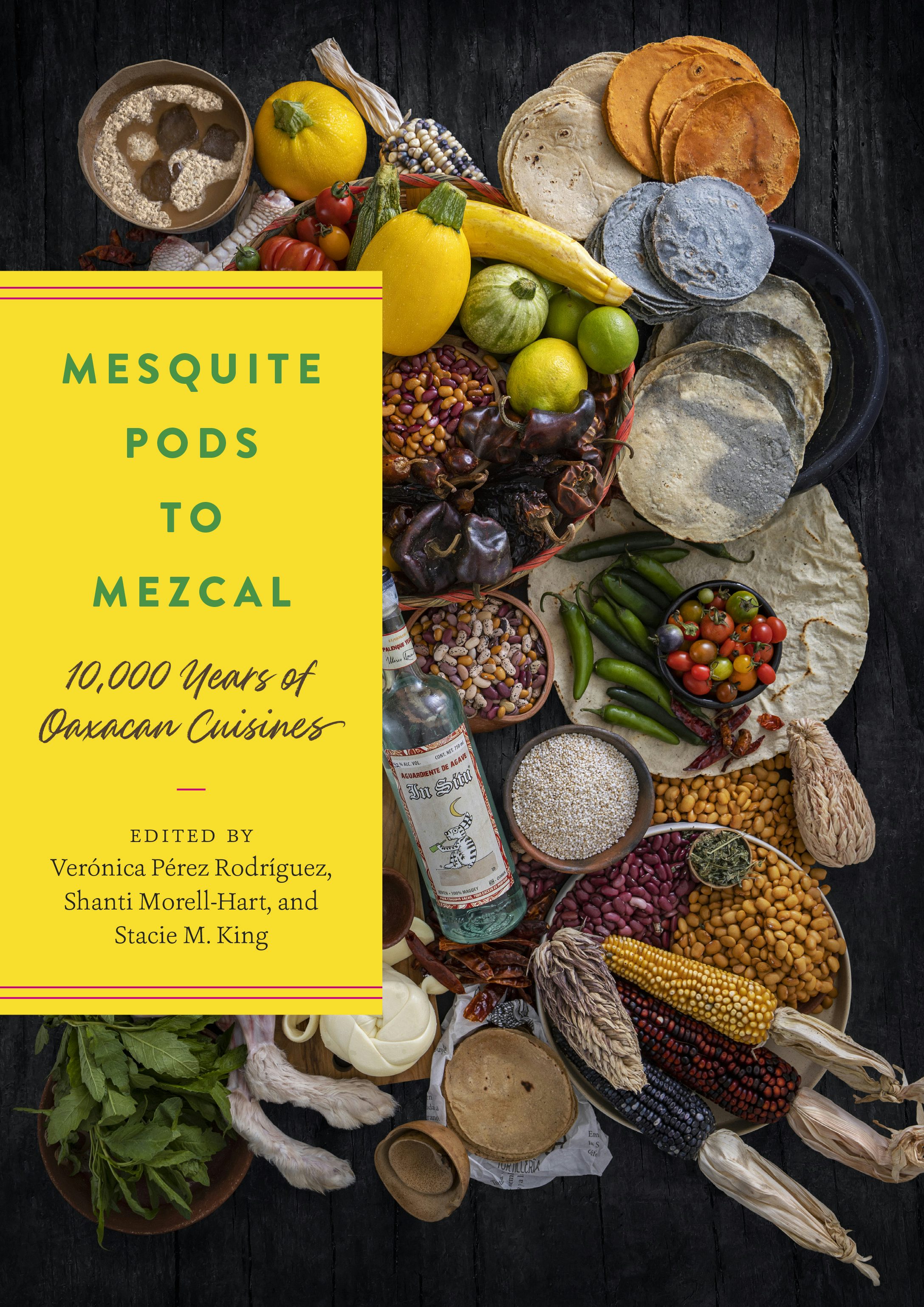

Among the richest culinary traditions in Mexico are those of the “eight regions” of the state of Oaxaca. Mesquite Pods to Mezcal: 10,000 Years of Oaxacan Cuisines brings together some of the most prominent scholars in Oaxacan archaeology and related fields to explore the evolution of the area’s world-renowned cuisines. In this new volume, authors cover the full spectrum of human occupation in Oaxaca, from the early Holocene to contemporary times. “The most exciting book to be published in the archaeology of food studies in a long time” (Traci Ardren, University of Miami), this volume boasts a diversity of archaeological methods and presents the first comprehensive look at the development of Oaxacan cuisines.

Read on to see what editors Verónica Pérez Rodríguez, Shanti Morell-Hart, and Stacie M. King have to say about the transformation of foodstuffs and foodways in Oaxaca, how archaeologists in the volume conducted research, and what gentrification means for Oaxacan cuisine and life today.

Mesquite Pods to Mezcal is available February 6 wherever you buy books! Go to our site to read the full table of contents today, and click the links to find more Latin American Studies and Food titles in our list.

I think we often assume that society changes or impacts food—how it moves, changes, and how tastes are made. But it seems that some of the research of Mesquite Pods to Mezcal points to the opposite, suggesting instead that food changes and impacts societies. How does that happen? In what ways does food dictate social structures and behaviors, and reinforce or challenge social and cultural norms?

Shanti Morell-Hart: At the small scale, our own dietary preferences impact our day-to-day behaviors, and different foods affect us in different ways. Some of these effects might be related to food allergies, or the ways that foods like caffeine affect our mood and behavior. But at the broader scale, we see religious food taboos shared by many people, and patterns in foods consumed in certain contexts (like a funeral). Many authors in this book argue for understanding how these cultural expectations and patterns in different kinds of food practices have impacts on someone’s health, their identities, their daily and spiritual practices, and their core understanding of the world. We consider how different food acts can help to uphold certain kinds of cultural norms, such as leaving food offerings for ancestors that sustain them in the afterlife. The flip side of the coin is: how can shifts in foodways—like a turn toward cultivation to supplement foraging—affect people’s lives beyond simply what they eat?

Stacie M. King: If we look specifically at mesquite pods and mezcal, on the one hand, mesquite pods are typically collected foods, wild collected foodstuffs, while mezcal is produced as a fermented beverage and has become a global phenomenon with some larger-scale, nearly industrial production. Mezcal received a Mexican national Denomination of Origin in 1994, and a Mexican regulatory council was established in 1997 to protect its quality. Many mezcals, but certainly not all, are produced in Oaxaca. But mezcal is perhaps one of the most important product and symbols of Oaxaca cuisine in the contemporary landscape. This contrasts with agave—a product that is literally taking over the Oaxacan landscape—and with mesquite pods, a wild collected food that has continued to be present in Oaxacan cuisine through millennia without much change. That is symbolic of both the longevity, creativity, and the capacity for transformation in Oaxacan cuisines.

Verónica Pérez Rodríguez: Some of the most intimate and unquestioned aspects of culture are our everyday habits, including those that have to do with food, what we eat, and how we eat it. What we find comforting to eat, acceptable or unacceptable to eat, is entrenched in us. We have all grown up in our own families and societies and these habits become part of who we are. The United States, for example, is a country where one can find a diversity of rich and ancient cuisines, because those of us who migrate here cannot help but bring our foodways with us. But behind our foods are food production systems—the ways we obtain food by hunting, gathering, foraging, farming—that have developed over millennia and have in turn shaped the way humans live and the way we leave our mark on this earth. For example, millions of people in Southeast Asia would not consider a meal to be complete without rice, and rice farming has transformed the landscape in many parts of the world. For Mesoamericans and for Oaxacans, no meal is complete without maize, without tortillas, and maize farming has dictated the rhythm of life in ancient Mesoamerica as it still does in modern-day Mexico. While transformations do occur, there is also something comforting and steady about keeping food traditions alive. In trying to keep things as they were, transformations happen, as one wants to make traditional dishes with the ingredients now available to us. Foods are transformed while trying to stay the same, and this is a powerful statement of the power of human will, resilience, and culture. Our book brings these complex and somewhat conflicting notions to life, while presenting the facts and details of how different ingredients, foods, and modes of subsistence and food preparation came into being and how they continue to be central to Oaxacan cuisines.

Most people might not think of foodstuffs when they think of archaeology. Describe some of the archaeological processes used in chapters throughout the book to study ancient, pre- and post-Columbian foodways and -stuffs in Oaxaca.

SMH: We are fortunate to have contributors who carry out so many different kinds of analysis. Some of the work in the book is more ethnographic, while other work is grounded in historical documents. Other data analysis is grounded in the residues that ancient inhabitants left behind. Some authors approach their data at a very macro level: How did people in the past modify their landscapes to cultivate food? What do those modifications look like today? Other authors pursue the kinds of traces that you can hold in your hand: fragments of culinary equipment like ceramic pots and obsidian blades; fragments of animal bones and charred seeds. Other contributors approach their questions from the very micro or even chemical scale: isotopic signatures left in the human skeleton; microscopic residues of starch grains extracted from culinary equipment. By taking so many approaches to the question of Oaxacan foodways, past and present, we can engage with many different kinds of food practices.

SMK: Archaeology, I think, helps to bring voices to people that haven’t been heard by revealing stories that might not show up in historical documents or in the stories we tell about the past. Archaeology can help us to identify the everyday actions and practices—including the making and eating of everyday meals—that were perhaps so mundane that they were left undocumented. The book includes studies that examine foods that were important to identities in different regions at different points in time, foods that were important to migrants and travelers, foods that were central to the urban project and urbanization across Oaxaca, foods that were considered valuable and worthy of protection during times of uncertainty such as during the early Colonial period, and foods that have become central to a sense of self with the onset of globalization and migration in the twentieth century.

VPR: I don’t have much to add, my colleagues have answered this question beautifully. Dr. Morell-Hart is a paleobotanist and an absolute expert on learning about the plant remains that may still be found in archaeological contexts. I am proud to say that the book is very complete, because there are chapters where we can learn about ancient foods and foodways resulting from all the methods currently available to us in archaeology, paleobotany, faunal analysis, isotope studies on human remains, starch grain analysis, ceramic and lithic analysis, and ethnographic and ethnohistorical information. Our book showcases what the cutting-edge methods are in the study of ancient foods.

What foods are integral to Oaxacan culture from an archaeological historical perspective? Are there foods which have functionally remained the same from pre-urban Oaxaca until today in some form?

SMH: Different ingredients in Oaxacan cuisines made their way in at different points in time, while others made their way out. Ingredients like acorns have fallen by the wayside, while maize went from an occasional foodstuff to a cornerstone of contemporary Oaxacan cuisines. We find ingredients like garlicky guajes and chile peppers that Oaxacan people have enjoyed as condiments and seasonings for thousands of years. We also find foods like venison and rabbit that vary in intensity based on availability and dietary preferences, but nonetheless are a pretty consistent part of the food lexicon.

VPR: Growing up in a Mexican and Oaxacan family I can say that no meal is complete without tortillas. This is not only exclusive for Oaxacans, of course. Grasshoppers are also something quintessentially Oaxacan, and although we grew up in northern Mexico because of my father’s job, he always made sure we had a jar of grasshoppers in the fridge to make our soups better. Though I find myself living in upstate New York now, there is thankfully a lively and growing community of Oaxacans; we all go out of our way, down to New Jersey, to secure tlayudas (large and rather tough tortillas that are unique to Oaxaca) and other ingredients to make Oaxacan dishes. The right chiles make any dish that much better. I also find that in our family the tradition lives on, there must always be tortillas in our refrigerator and my kids don´t seem to be able to go a day without eating something wrapped in a tortilla. Looking at our family makes me realize that what is presented in our book is true and essential, and has been for thousands of years. Our foods are central to our identities and wellbeing and even though we travel, we take our itacates with us and stubbornly cling to the foods that make us whole and that comfort us. It’s very powerful that we have been able to see this in the archaeological record, that foodways are long time in the making, and that despite the many social and political transformations the people of Oaxaca have faced, their foods have laid the foundation for their lives and success for thousands of years.

Can you talk about how globalization and gentrification impact and interact with the latter part of this volume? And, more generally, what the presence of these forces means for Oaxacan culture and cuisines?

SMH: Processes of globalization affect local cuisines by extracting local ingredients like wild agaves for global mezcal production, and by transforming culinary preferences for Oaxacan people, such as the push to shift from tejate to soda. In this way, globalization can adversely affect health outcomes and cultural traditions, but also put treasured foodstuffs and foodways out of reach of the communities that have developed them for generations.

SMK: In many ways, traditional Oaxacan cuisines have never been so highly regarded. The gentrification that is happening in Oaxaca is making many restaurants there out of reach of the average Oaxacan. This has also happened with mezcal. Mezcal has become so valuable as an export commodity that it has become too expensive for locals to consume. This is a potential the danger of the marketization of Oaxacan cuisines. Yet, Oaxaca thrives as a tourist destination in large part because of its cuisine, markets, and “traditions.”

VPR: This is a hot button issue in Oaxaca today. The global boom for mezcal is having huge economic and environmental impacts on Oaxacan lands, people, and economies. While we are all happy and proud that our Oaxacan cuisines and mezcales are appreciated by the world, we are also nervous about how this boom is being handled and lived by Oaxacans, maestro and maestra mezcaleras, and farmers. There is also a lot of debate among Oaxacans regarding who gets to present what Oaxacan cuisines are to the world. Is it done by professional chefs with formal training and outside experience, or the traditional cooks, most often women, who have been keeping these recipes alive for generations? Also, while traditional cooks may be appreciated, more often than not these cooks don’t benefit financially from the work they do, not in the way that more renowned chefs and English-language cookbook writers have profited from the global boom for Oaxacan cuisines and spirits. On the other hand, the Oaxacan diaspora in the US has expanded the reach of this region and its cuisines, and this has made the lives of many Oaxacan immigrants possible and richer while abroad. It is a point of pride to see one’s cuisine loved and appreciated, as long as this does not result in alienating Oaxacans from their own cuisines, foods, and traditions. Change is inevitable and it will be up to us, Oaxacans and Oaxacan food appreciators, to negotiate the complexities of this situation. I believe it can be done if we are brave, honest, and critically conscious of the ramifications of our actions.

Why is this history important right now? What political, social, and cultural contexts felt pertinent during the compilation of this volume?

SMH: The book comes at a key time when culinary traditions are nominated for UNESCO status every year, a fraught process that can establish legitimacy and garner protections for food producers, but also “fossilize” foodways that have undergone improvisation for thousands of years. One goal of this book is to highlight the ingenuity of Oaxacan food producers over time. It wasn’t a question of people following a frozen template for generations, but rather engaging with food in a very dynamic way. We also wanted to highlight the diversity of culinary traditions in Oaxaca, not only from culture to culture, but over time. There have been countless Oaxacan cuisines!

SMK: Oaxaca is unique, as I tell my students, because “Oaxacan-ness” is valued both by Oaxacans and by outsiders who visit Oaxaca. Oaxaca has long been the place to go for the purchase of traditional crafts, to visit traditional markets and archaeological sites, to view traditional dance, and to eat traditional foods. Nonetheless, there are struggles with racism and classism within Oaxaca that extend down to food, and have impacted diets throughout the last centuries, creating dietary changes that trend alongside global changes. At the same time, there has been this very early push to market and celebrate Oaxacan cuisine, which was thoroughly embraced locally.

VPR: I share in the opinions of my coauthors, and I would love to see this volume also published in Spanish also because among the Spanish speaking public in Oaxaca, in Mexico, and beyond there are important debates taking place regarding the crossroads that face Oaxaca and Oaxacans today. This book hopefully contributes to larger conversations where we are aware of our long and rich history and how we want to take the present and the future of our food traditions into our own hands in an ever- changing, globalized, and commodified world that seeks to package everything for massive sale and consumption. Oaxaca and its food traditions are rich and deep, and should withstand those perils.

Verónica Pérez Rodríguez is an associate professor of anthropology at the University of Albany, SUNY.

Shanti Morell-Hart is an associate professor of anthropology at Brown University.

Stacie M. King is a professor of anthropology at Indiana University.