Excerpts from Mario Barradas and Son Jarocho: The Journey of a Mexican Regional Music

Mario Barradas’ influence on Son Jarocho music is undeniable. From its rural origins in the Sotavento region, to Mexico City, a history of modern Son Jarocho music can be traced through the narrative of Barradas’ life. Barradas also played a role in increasing the style’s popularity, introducing Son Jarocho music to new audiences through radio and cinema. To understand Son Jarocho music is to understand its roots, but were Barradas’ personal and musical roots?

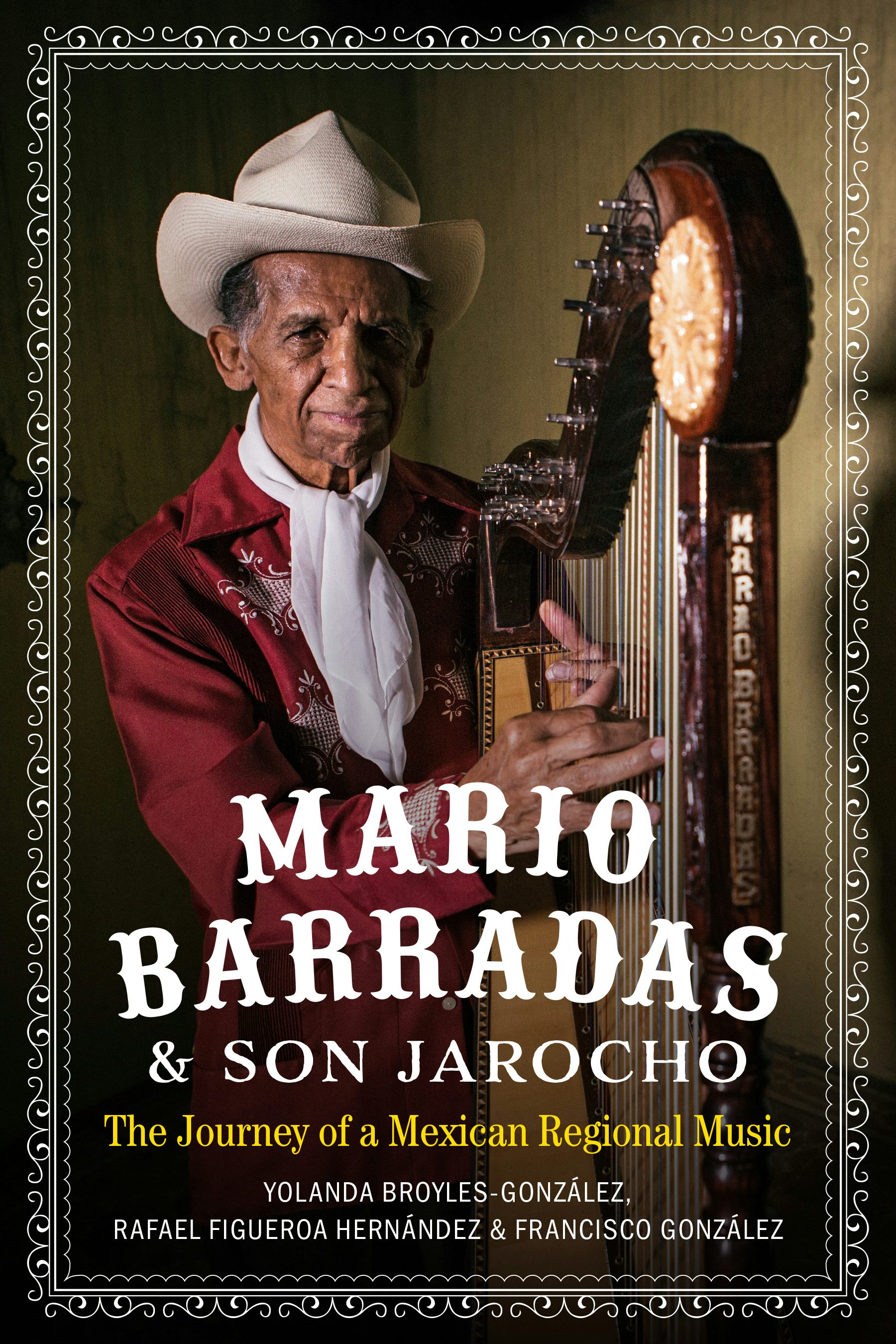

New book Mario Barradas and Son Jarocho: The Journey of a Mexican Regional Music by Yolanda Broyles-González, Francisco González and Rafael Figueroa Hernández begins with an oral history by Mario Barradas himself. We are pleased to share a few anecdotes from his life, as he told them himself, in the selected excerpts below.

Excerpts from Mario Barradas’s Life in Music by Mario Barradas

Barradas’ Uncle Santiago Barradas Díaz

I am going to talk a little about my father’s brother, Santiago Barradas Díaz. He played harp; he really loved the harp. Around 1926, he and my father started working on the railroad tracks as day laborers. They earned between eighty and ninety centavos an hour, starting at six in the morning, working twelve-hour shifts. They had no medical services and no hospitals. There was

nothing.

My father, Manuel, wanted to play harp, but my grandmother would tell him, “No, no, you shouldn’t play harp. Santiago plays harp, so you should learn to play jarana.¹ That way you won’t have to look outside the family for someone who plays jarana. That way the money stays here. If you earn five pesos, you don’t have to give half to someone else.”

In order to learn jarana, my father and uncle had to saddle up their horses and ride more than five kilometers to their lessons. They say my father only went once, and from that one lesson he learned to play jarana, even though it had gut strings that easily went out of tune. They say my father took a pencil with him, and when the jarana teacher showed him how to tune, he marked the strings over one of the frets when it was in tune. After my father did that, he could tighten the strings until the pencil marks reached the right place. My father never went back to the jarana player.

My uncle Santiago was so obsessed with the harp that he ended up dying from lung illness. My father used to say that they would get home after working twelve hours on the train tracks, and my uncle would grab the harp and forget to eat. He ruined his health and died young of pulmonary illness. That was Santiago Barradas Díaz, my father’s brother.

Learning Business

When I was learning to play the harp, my parents sent me to Playa Vicente to learn about business. I wasn’t with the railroad yet. My mother’s family—my aunts and uncles—owned a store, a billiard hall, a bar, and a soda fountain. My parents sent me there. I was already playing the harp, but I didn’t take a harp with me, or anything else. Sometimes I worked as a coime, the person in charge of the billiards. Other times I was a clerk in the store. I didn’t like it when my relatives would send me all the way to the Tesechoacán River to bring water. I had to walk six hundred meters with large tin cans to look for water. I would tell myself, “Well, I came to learn the commerce business, but they send me looking for water.” What had happened is that the lady who lived across the street used to give them water, but they had a falling out with her and I was the one who paid the price. After about six months, I was desperate to return to Tierra Blanca. Even though I only knew around eight sones—slow sones— and one or two boleritos,² I wanted to continue playing the harp. Learning about business really didn’t interest me. Every day I thought, “What can I do to return to Tierra Blanca without hurting my family’s feelings?” One day I finally came up with a plan. In the spot where I fetched water, the river was deep and the bank was just steep rocks. One day, I went to the river and came back without the water cans. My family said, “What happened to you? What happened?”

I told them, “I almost drowned! I bent down to get the water and I slipped. I thought it best to just let the cans go. The only things left were the stick and the chains, but the cans were taken by the water.”

“Well,” they said, “it happened. It’s done!”

I waited about fifteen days, so as not to tell them right away that I wanted to return to Tierra Blanca. Then I told my uncle, “So, I want to go back to Tierra Blanca. Can I, or what?”

“Yes, son. If you feel like you want to go back, why not? Take down four shirts, four pairs of pants, and two pairs of shoes.” They furnished me with everything and even gave me a little money. They put me on a riverboat at Playa Vicente. It took me to Villa Azueta, where I waited for the train, which finally got me back to Tierra Blanca. That was around 1940.

Making Gut Strings

Making gut strings for musical instruments is a beautiful process. I know because I would accompany my father when he made gut strings. He would look for gut during the quarter waning lunar phase. If you don’t harvest the gut during that phase of the moon, the strings will break. It’s the same when you cut wood from a tree. If you don’t cut it when the moon is in its crescent waning phase, the wood will rot. My father used to say, “There’s a good moon right now, so I’m going to buy some gut.” He would buy the gut and take it away in a bucket.

The best gut comes from sheep, but cow gut also works. First you take out the little inner thread; you use your fingernail to look for it, and you take it out. Then you scrape off the flesh and wrinkles, cutting from end to end. Sometimes little air bubbles will form, and you must use a needle to pop them. We would start at 7:00 a.m., and by 1:00 p.m. we were already stretching the strings according to the thickness needed for each bass string. If you want thick strings, you gather three, four, even five strands of gut and twist the strands together with a loop. Stretch the strings until they’re tight, and in about three minutes they are loose again. Then you have to retighten them. When the strings begin to stay tight, you sand them so that they come out round. After sanding, the string stretches again, and when the string is more or less ready, you rub beeswax on it with a chamois. Once it starts to squeak, you stretch it again. As soon as it becomes transparent, the string is ready to use.

Read more of Barradas’ story in Mario Barradas and Son Jarocho: The Journey of a Mexican Regional Music

Notes:

- The jarana family of stringed instruments is part of the rhythmic-harmonic component of the music of Sotavento. They are strummed and vary in size and pitch. A jaranero is the person who plays the jarana.

- Boleritos means little boleros. In modern Mexican usage, the term “bolero” refers to a romantic ballad that evolved from the Cuban style into an urban Mexican and Latin American genre performed by guitar trios and quartets. The Mexican bolero is exemplified by Trío Los Panchos, Los Tres Reyes, and Los Dandys, among other groups.