This week, Travis Audubon is sponsoring an exclusive book launch for Victor Emanuel’s new book One More Warbler: A Life with Birds, in partnership with the University of Texas Press. Victor, the founder of the largest avian ecotourism company on earth, will be interviewed by New York Times bestselling author Stephen Harrigan. Former First Lady and birder, book-lover Laura W. Bush will make opening remarks.

Victor’s memoir shares his journey from inspired youth to world’s top birder including his biggest adventures, rarest finds, and the people who mentored and encouraged his birding passion along the way. We asked writer, editor, and teacher S. Kirk Walsh to reflect on what Victor taught her.

Ways of Seeing

By S. Kirk Walsh

Prior to working with Victor Emanuel on One More Warbler, I had gone birding once with my family at Point Pelee, a Canadian national park that narrows into a sharp point of silt and sand on the northern boundary of Lake Erie. Given its location, the park offers a natural resting spot for warblers during their annual spring migration. It was an overcast day in early May, and we spotted over 30 species, 10 of them were warblers, including the Blackburnian Warbler and the Tennessee Warbler. Afterward, I wrote a first-person essay about my father, our changing relationship, and the birds for The New York Times. Several years later, this piece inspired my introduction by Jim and Hester Magnuson to Victor, and the job of writing and collaborating with him on One More Warbler.

For almost two years, we met on a regular basis at his house in Travis Heights, recording interviews about his adventures in Texas and around the world, and then I’d return with drafts of chapters that Victor and I would review and edit together. As we moved further into the project, I knew that I needed to go birding with Victor to truly understand his passion and love for birds. Since several chapters mentioned the Bolivar Peninsula and the nearby stretches of Texas Coast, where Victor had experienced his first birding adventures, I suggested that we take a trip to his cottage there.

We agreed on a weekend in November of 2015, and my husband, Michael, joined us. We departed Austin on a Saturday morning in two cars (since Michael and I were planning to stay on for an extra night). For our route, Victor decided on Highway 71 East to Columbus, where we detoured onto back roads, so we could pass through Freeport, where he started his famous Christmas Bird Count in 1957. At lunchtime, we stopped in Eagle Lake near an antiques store and ate our sandwiches on the opened gate of Michael’s pickup. As we ate, Victor looked up and admired the passing cloud formations—wispy brush strokes against the blue sky. “Hmm-hum,” Victor uttered, staring up at the clouds. “Hmmm.” It was what I understood to be a Victor moment, a moment where he is caught in a spell of admiration, the way he appreciates the ordinary and the extraordinary with equal measure and wonder.

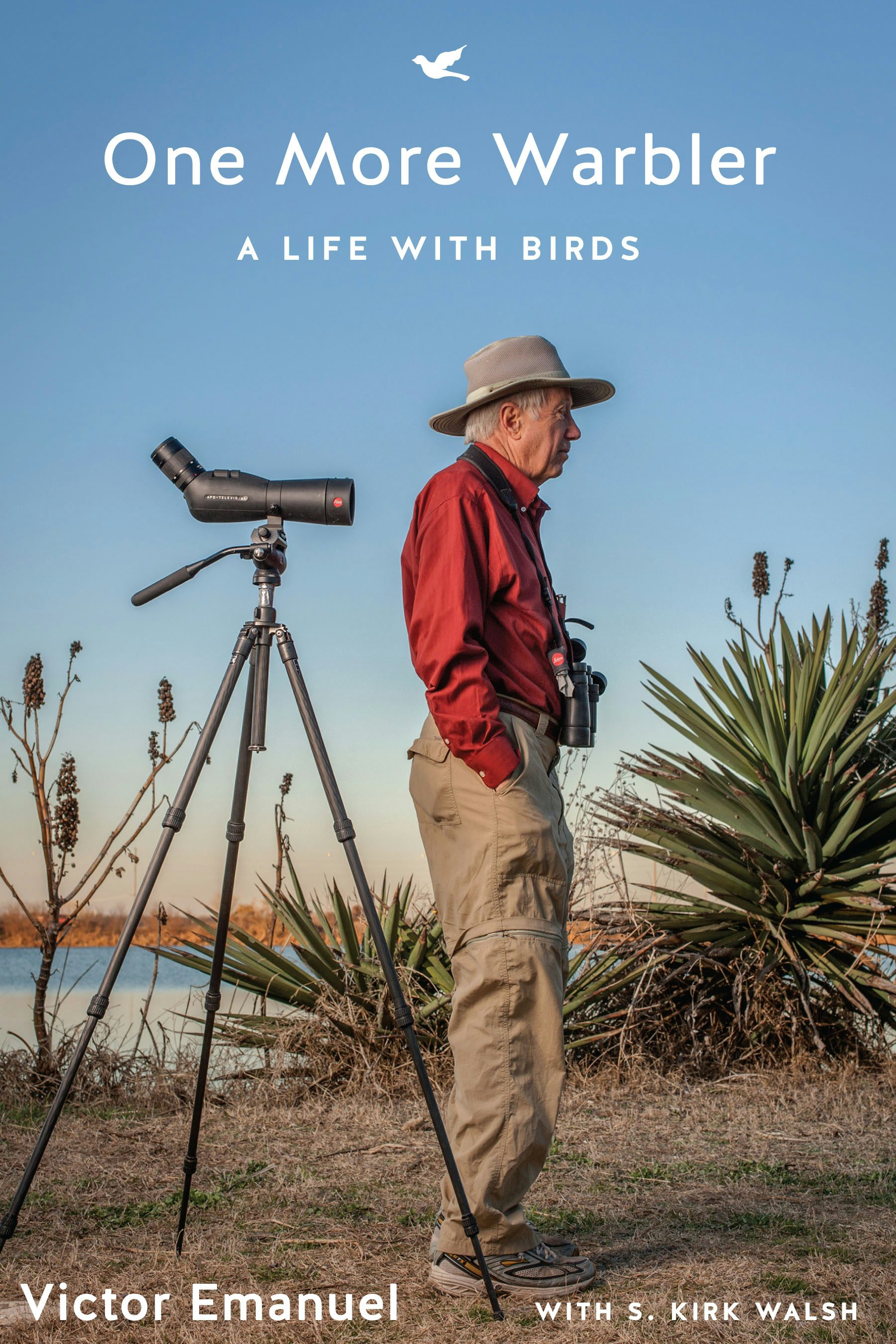

Photo by S. Kirk Walsh

After lunch, I joined Victor in his SUV so he could supply commentary as we drove closer to Lake Jackson and Freeport. Victor had brought a pair of walkie-talkies so we could communicate with Michael as we continued to drive south. Red-tailed hawks and vultures cut wide circles in the sky. The rolling terrain gave way to flat stretches of marshland and fields. An occasional egret waded in a roadside ditch. The sturdy necks of little bluestem bent in the November breeze. Victor showed us the Justin Hurst Wildlife Refuge, a 10,311-acre area west of Freeport and Jones Creek, where he took George Plimpton when they first met and George was reporting on the Freeport Christmas Count for Audubon Magazine in 1973. The landscape is abundant with yaupon, live oaks, and locus trees, which attract a wide variety of birds with its leaf litter and insects. A few minutes later, we drove past Sheriff’s Woods, populated with short scrubby oaks and other native species. It was here that Victor was parked on the afternoon of September 26th, 2003, and, tuned into his car’s radio, heard Peter Matthiessen talking about his memories of his dear friend, George Plimpton, because he had just passed away. “It was a strange coincidence, hearing Peter talk about George, and learning about his death in this spot,” remembered Victor.

Photo by S. Kirk Walsh

As we crossed over to Galveston Island, fleets of Brown Pelicans floated in the air. The blues, greens, and browns of the causeway and Gulf Bay unfurled on either side of the bridge. We continued along the narrow island, and Victor abruptly stopped on the side of the road. Michael followed suit, and Victor unloaded and set up his scope on the grassy shoulder facing the causeway. For a better view, Michael suggested setting up the tripod on the bed of his truck. Victor nodded, and the three of us jumped onto the bed. With the scope, Victor caught a Roseate Spoonbill wading in the marsh grasses. The bird was a breathtaking sight with its deep pink feathers and flat, spoon-shaped bill. We each got good looks. Though this species is a common sight in this region (and can be found on billboards advertising tourism for the Bolivar Peninsula), it was the first one that Michael and I had ever seen—and there was a palpable sense of victory and elation.

By two o’clock, we arrived at the loading area for the ferry and its three-mile crossing to Port Bolivar. As the ferry motored out of its slip, multi-story freighters, container ships, and cruise ships, looking like industrial layered cakes, navigated through the channel’s waters. The familiar logos of Dow and BASF were emblazoned on the bows of the ships. The skeleton-like silhouettes of the oil refineries of Texas City could be seen in the distance. A flurry of gulls and pelicans stitched the sky. A school of dolphins arched through the waters.

Within minutes, the shadowy outline of Port Bolivar—and its lighthouse built in 1860—became visible. The peninsula is a 35-mile finger of land, composed of sand and low-laying marsh that extends from the ferry landing to the small town of Gilchrist to the north. The devastation of Hurricane Ike is still evident throughout much of the area with several unrepaired homes and abandoned motels, like lingering ghosts. Here and there, concrete foundations lay exposed, and flights of stairs lead to nowhere. A few miles away from the ferry landing, we arrived at Victor’s cottage, Warbler’s Roost. It was exactly as I had imagined in it: a modest, yellow-painted cottage on 10-foot stilts with a large porch that overlooked the Gulf of Mexico, marsh lands of reeds, canes, and sedges, and the nearby North Jetty.

Upon our arrival, Victor gave us a brief tour of Bolivar, showing us the ponds and inlets on the other side of the peninsula. He cut the ignition after spotting an American Oystercatcher feeding along the edges of the Horseshoe Marsh Bird Sanctuary. With its long bright red bill, this shorebird is not an everyday sight, and Victor was thrilled to point out the striking species with its bold black head, white underside, and stout legs. During the evening, we walked along the five-mile North Jetty. Locals—sitting on wheeled coolers and listening to boom boxes—fish for redfish and southern flounder. Meanwhile, hundreds of American Avocets, herons, gulls, egrets, and other seabirds assembled on the shallow flats. Small armies of white pelicans preened between the cuts of grass. As we walked in silence, the oranges and reds of the sun saturated the landscape as it slipped behind the western edge of Galveston. A line of tankers and cruise ships motored out of the channel. Oilrigs perforated the distant horizon. For me, it was a compelling juxtaposition, this unusual landscape where natural beauty and manmade industry reside so closely to each other. I quickly realized that Bolivar isn’t your traditional spot of seaside charm. Instead, it’s a place of grit, survival, and wild beauty.

Photo by S. Kirk Walsh

Our first morning, we woke at five-thirty. Victor was already awake, and the scope and three plastic chairs were already arranged on the porch. Before the sun rose, our only companions were the morning darkness and bright stars as we sipped tea and coffee. Then, an unbroken band of red stretched across the horizon. It steadily faded into tangerine orange layered with a brilliant yellow until the only color was a glowing spot of red where the sun eventually emerged. The sight was quiet and operatic all at once.

Little did Michael and I know that this was just a prelude to the real show that was about to occur: In the shifting shadows in front of Victor’s cottage, the dark shapes of hundreds of birds began to emerge, walking and swimming along the shallow mud flats. Golden light began to splinter through the feathery tops of spartina grass and sedges, and a number of elegant, long-necked egrets and herons dotted the marsh, slipping slivery fish down their long, thin throats. Victor caught many species through the scope, identifying them and then allowing Michael and me to see them firsthand: American Avocets, Marbled Godwits, Willets, Laughing Gulls, Dowitchers, Dulins, Black Skimmers, and many more. Thousands of these birds congregated in deep, scattered rows across the flats. Skimmers performed a synchronized dance—lifting up in enormous masses, circling the morning air, and then returning to a nearby spot on the flats. It was a rush of changing patterns. I had never seen anything like it before.

Photo by Mike Dolan

This first morning on Victor’s porch opened up something for Michael and me. He introduced us to the complex and beautiful world of Bolivar that we never knew existed. As Victor had said to me more than once, spending time on the porch of Warbler’s Roost created a certain peace and transported him far away from the world’s troubles. I experienced a similar kind of peace, almost a cellular configuration in my body, producing a calm and ease. I had worries on my mind—a sick parent, other stresses in my extended family, work deadlines, the recent terrorist attacks on Paris, the rise of Donald Trump as the GOP candidate. . . All of these concerns receded and rested in a different part of my brain, while my attention stayed focused on this extraordinary parade of nature.

That afternoon, Victor took us to the beach. We drove along the hard-packed sand and then took a short walk on the beach. Tangles of seaweed—and scattered bits and pieces of nondescript trash—washed up in the foaming surf. Victor instructed Michael and I to sweep our binoculars along a row of sea- and shorebirds. As we moved our glasses along the line of birds, he named the species one by one: a Laughing Gull, a Royal Tern, a Snowy Plover, a Forester’s Tern, and a Caspian Tern. It was amazing how easily Victor distinguished the birds—all of the species white but with variations of markings, bill shapes, and leg color.

Photo by S. Kirk Walsh

We continued along Highway 87, a two-lane road that circled up to High Island. On one side, the Gulf crashed against the shoreline, precariously close to the concrete barriers, and then on the other side, whitecaps flecked the waters of the Intracoastal Waterway. Even before I met Victor, I had heard about High Island as being one of the best birding destinations in the country during the spring migration. As most people know, High Island isn’t an island at all, but an elevated salt dome that provides the first resting spot for migrants who are flying north from Central and South America. At first glance, the slightly elevated area merely looks like a dense stand of forests, pine trees, and scrubby oaks.

Before eating our picnic lunch at High Island’s Boy Scout Woods Sanctuary, Victor showed us the rustic amphitheater of bleachers that overlooks a water drip at the foot of a cypress tree. In April, Victor explained, the bleachers are crowded with birdwatchers as they take in the migrants rinsing salt from their feathers from the flight across the Gulf and to sate their thirst for the next leg of their journey. On this day, a Yellow-bellied Sapsucker tapped away on one of the crooked branches of a nearby oak tree. On another bush, an Eastern Phoebe flitted from branch to branch. Overhead, we spotted a juvenile Bald Eagle soaring near the High Island water tower.

As we ate our lunch of apples, slices of cheddar cheese, crunchy tostadas, and squares of chocolate, Victor continued to point out spots of interest that we had written about in the memoir. Just a few feet away, he noted where Peter Matthiessen, Barry Lyon, and he witnessed the fallout of warblers during one of Peter’s last visits to the Texas Coast before he passed in 2014. “There were warblers everywhere,” Victor remembered. “It seemed like it would never end.”

Photo by S. Kirk Walsh

After lunch, we drove to the 34,000-acre Anahuac National Wildlife Refuge, about 17 miles away from High Island. On the way, we made several stops along State Road 124 to observe raptors perched on utility poles. By this time, I’d gotten used to the abrupt stops and setting up the scope, so we can all get good looks of the various birds: American Kestrels, White-tailed Kites, Crested Caracaras, and Red-tailed Hawks. When we arrived at the preserve, we took a short walk along the boardwalks that intersected the refuge’s marshlands. There, we took in the dramatic sighting of a Vermilion Flycatcher, its vivid red cap fluttering in the breeze. A small stroke of brilliant color against the sandy and virescent vista. Then, we drove around the two-and-a-half-mile look that encircles Shoveler Pond, a 220-acre freshwater impoundment of teeming wildlife. Even before we observed the birds, we could hear the animated chorus of waterfowl amid the tall reeds. Flocks of numerous birds sunned on the shoreline and waded through the marshlands: Fulvous Whistling Ducks, Black-bellied Ducks, Common Gallinules, Least and American Bitterns, and many others. We spotted several alligators, their hooded eyes breaking the water’s surface.

By the end of our two days with Victor on the coast, we had observed over a hundred feathered species. It was inspiring and breathtaking. The weekend certainly provided a crash course in birding and the Texas Coast. Also, it gave me the invaluable opportunity to witness Victor in his natural element—his world, his patch.

Since this inaugural trip to Bolivar, I have returned two other times—once with Michael during a spring break, and once with my sister and her husband for Christmas Day. Within the short span of two years, birds—and Bolivar—have taken on new meaning in my life. Working with Victor has given me a different way of seeing the world. Both on the coast and in my neighborhood, there is a moment of delight when I recognize a certain species: Just the other evening, Michael and I took in the looping flight patterns of Common Nighthawks in the dim half-light of our neighborhood, the white patches on their underwings looking like fleeting flashes of illumination; or the sole Cedar Waxwing soaring across a trail at Mueller Park, with the setting sun striking its pale yellow breast. And each time, Michael and I turn to each other and say, with a sense of wonder and appreciation, “Did you see that?”

Photo by S. Kirk Walsh