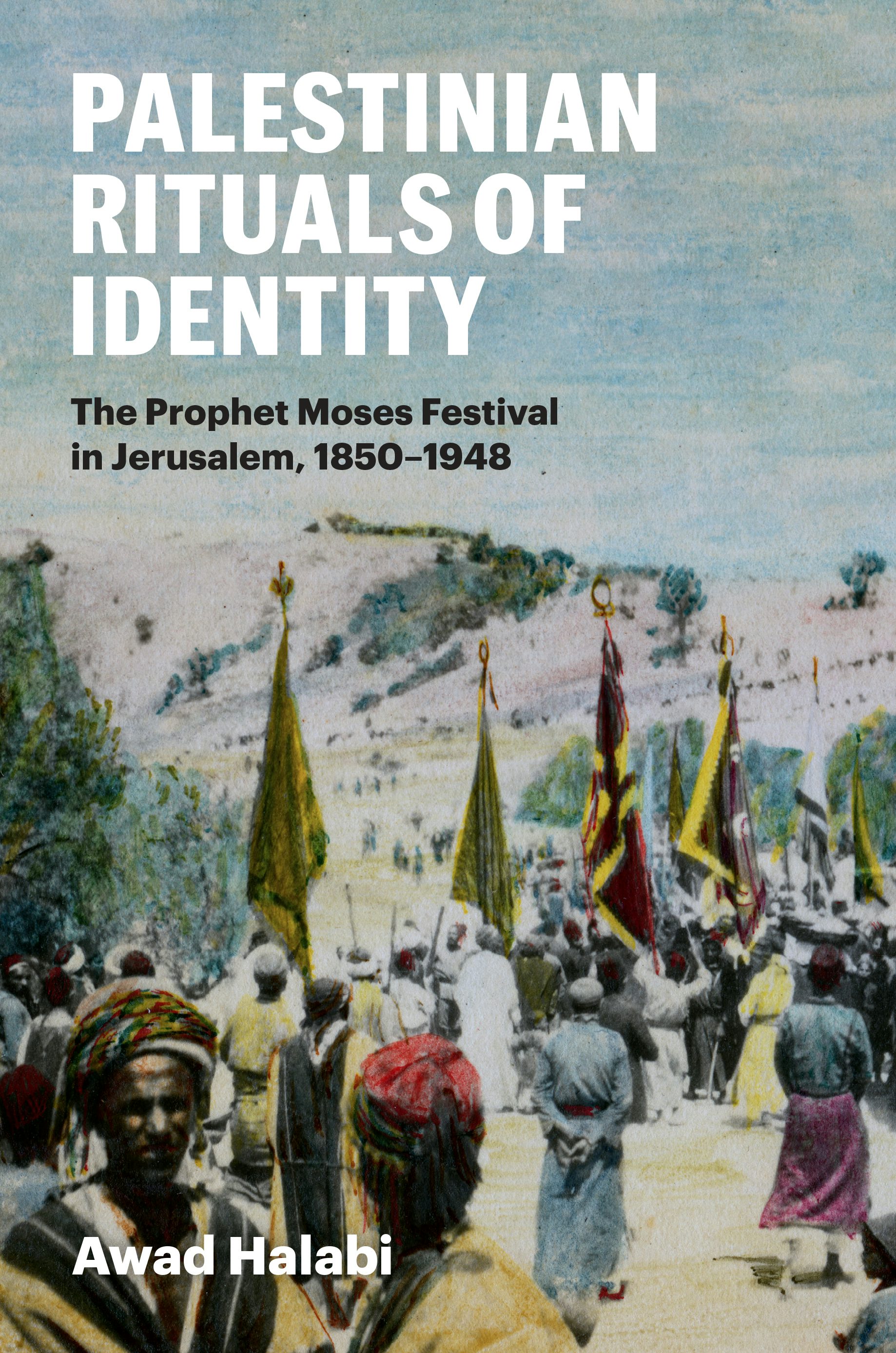

Members of Palestine’s Muslim community have long honored al-Nabi Musa, or the Prophet Moses. Since the thirteenth century, they have celebrated at a shrine near Jericho believed to be the location of Moses’s tomb; in the mid-nineteenth century, they organized a civic festival in Jerusalem to honor this prophet. Awad Halabi’s new book Palestinian Rituals of Identity: The Prophet Moses Festival in Jerusalem, 1850-1948 takes an innovative approach to the study of Palestine’s modern history and Palestinian identity by focusing on the Prophet Moses festival from the late Ottoman period through the era of British rule.

In the book, Dr. Halabi explores how the festival served as an arena of competing discourses, with various social groups attempting to control its symbols. Tackling questions about modernity, colonialism, gender relations, and identity, Halabi recounts how peasants, Bedouins, rural women, and Sufis sought to influence the festival even as Ottoman authorities, British colonists, Muslim clerics, and Palestinian national leaders did the same.

Below, we asked Dr. Halabi some questions about his book and research. This week is the annual meeting of the Middle Eastern Studies Association and we’re offering 30% off and free domestic shipping on titles featured during the conference. Use discount code UTXMESA during checkout on our website!

What inspired you to write this book, and was there anything that surprised you as conducted research?

I was initially interested in Palestine’s modern history, from the mid-nineteenth to the mid-twentieth century, and in reading on the subject, I periodically came across references to the Nabi Musa (Prophet Moses) festival, the event either mentioned tangentially by historians or recorded in firsthand accounts (visitors to Palestine frequently spoke of it in their memoirs or reflections of life in Palestine before 1948). Writers typically mentioned the festival when discussing matters such as officials’ participation during the late Ottoman era, the so-called Nabi Musa Riots of 1920, and the involvement of Palestine’s leading nationalist figures and activists. But the few works that examined it surveyed the festival only broadly. In addition, I became interested in religious, anthropological, and sociological works that provide interesting methodologies for approaching rituals and festivals. These approaches eventually prompted me to ask new questions about the festival and its place in Palestine’s modern history. I began to see the festival as a microcosm for understanding that history.

While researching the subject, I was surprised to learn that the British kept a close watch over the festival both because it was the largest public religious celebration in Palestine and because they wanted to remain culturally connected to the Palestinian Muslim community so as to appear respectful of the region’s Islamic culture.

I was also surprised to find a large trove of evidence, including Islamic court records documenting expenses for the festival and repairs at the Prophet Moses shrine dating back to the sixteenth century. Although I found only a few relevant Ottoman documents, the British kept extensive records documenting their efforts to keep tabs on the festival; in addition, Arabic-language newspapers regularly covered the ceremonies.

The Nabi Musa shrine will mean different things to different people. Can you outline what you find to be the religious significance of both the shrine and Nabi Musa himself?

Islam, of course, reveres several figures as prophets, among them Abraham, David, and Isaac, as well as Jesus, Mary, and John the Baptist The Qur’an regards Moses, too, as one of God’s prophets; the Qur’an mentions him more often than it does any other human. Muslims throughout history have thus erected shrines to venerate these holy figures. Some of these shrines are linked to the tombs of such figures; others may commemorate a place where a holy figure died or performed a miracle. Since the thirteenth century, Muslims have venerated a shrine dedicated to the tomb of the Prophet Moses, located southeast of Jerusalem and west of Jericho (even though four other tombs, in Jordan and Syria, also claim that title). They held annual celebrations (s. mawsim) to honor Moses’s resting place.

For Muslims, the tomb is a source of blessings (baraka). The annual Nabi Musa festival, held during the Greek Orthodox Church’s Easter week celebration, attracted thousands of pilgrims each year (many Muslim celebrations are tied to that church’s fixed solar calendar). Muslims performed various forms of worship at the shrine, such as venerating the tomb, lighting votive candles, and engaging in Sufi mystical practices; they also enjoyed performing folk dances and singing folk songs. In the mid-nineteenth century, Ottoman authorities in Jerusalem mandated that the festival begin first in Jerusalem, requiring pilgrims to convene in Jerusalem to highlight the new political authority of urban notables and the Ottoman state. Under British rule, from the end of World War I to 1948, the ceremonies continued to begin in Jerusalem. Muslims from throughout the country would congregate in the city before descending to the shrine, located below sea level, worshiping there for a few days to a week. Palestinians, particularly rural people and the Bedouin, maintained a strong attachment to the Moses shrine, much more than they did to the urban-based pageant in Jerusalem. After 1939, the British imposed restrictions on the festival and its public celebrations in Jerusalem, but rural people remained devoted to worshiping at the shrine.

How have Palestinians shaped the festival to reflect a growing national identity while at the same time adapting to Western values and mores?

Different social groups used the festival in various ways to serve their own objectives. One such objective was to help craft an emerging Palestinian national identity. Since the thirteenth century, Muslim pilgrims traditionally visited the shrine itself, going directly to its site near Jericho. Again, when members of Jerusalem’s municipal council took over organization of the festival, in the mid-nineteenth century, they required pilgrims to arrive in Jerusalem and partake in ceremonies that highlighted the role of town elites, Ottoman officials, and municipal leaders. Pilgrims arrived in village contingents, raising the banners and flags of their villages and town. These new, modern ceremonies confirmed the power dynamics between urban elites and rural pilgrims. The pilgrims would then visit the Moses shrine for a weeklong ceremony.

After World War I, when the modern state of Palestine began taking shape, the festival was increasingly incorporated into the emerging Palestinian national identity. Nationalist groups spread nationalist messages, chanted nationalist slogans, and promoted nationalist politics to the thousands of pilgrims who attended in Jerusalem. In 1929, the Palestinian leader al-Hajj Amin al-Husayni began inviting Palestinians from areas that had not traditionally participated in the festival, such as the country’s northern part and along its coast. He invited youths and Boy Scout troops from Jaffa and Haifa to march in the parade. Arabic-language newspapers noted how the arrival of pilgrims from throughout the country confirmed an image of a unified nation, joining together in a common celebration but also asserting their nationalist demands.

How did British colonialism affect the festival?

The British influenced the festival significantly, for they immediately recognized its importance as a major public Islamic celebration. High-ranking British officials involved themselves beginning in 1918, the first celebration held after the end of Ottoman rule, when they participated in the religious ceremonies and played roles that Ottoman officials had had previously performed. For example, they ordered their military band to participate in the procession of pilgrims, just as the Ottoman military band had done. The British remained active and visible members of the festival because doing so gave the impression that they were respectful guardians of Palestine’s Islamic culture at a time when Arab opposition to British support of Zionism and Jewish immigration to the country was growing. Beyond that, the British remodeled the ceremonies in the late 1930s. After they quashed the 1936–1939 Arab Revolt, they wanted to maintain the festival but suppress its nationalist messages. In 1939, they prohibited pilgrims from entering the Old City of Jerusalem in great crowds. After 1939, moreover, only a select group of Arab and British officials were permitted to participate in the festival’s opening and closing ceremonies. The British thus passed restrictions that truncated the festival, limited who could participate, and restricted the movement of crowds and pilgrims as a way to prevent the festival from evoking anti-British and Palestinian nationalist messages.

Beyond the leaders, elites, and colonial officials, how have nonelites, such as peasants, Bedouins, women, and communist Jews, articulated their own social and political concerns?

Nonelite groups understood and related to the festival differently than elite participants did. Rural pilgrims, such as villagers, women, and Bedouins, understood the festival as a religious ritual that honored a revered Qur’anic prophet. Again, members of these nonelite groups believed that they could acquire the baraka (blessing) of the Prophet Moses when visiting his tomb and shrine. Many pilgrims brought their families to the festival, which was seen as a family affair, and women generally attended in higher numbers than men, particularly because they could petition Moses to heal a sick child or overcome infertility problems. Further, pilgrims, both men and women, engaged in folk and rural traditions, such as dancing and singing, and the Bedouins put on displays of their prowess in activities such as horseracing and falconry. Later, in the 1930s, pilgrims could enjoy watching “movie boxes.” At the shrine, where they remained for three to seven days, they ate foods they rarely got to enjoy, such as meat and ice cream. This food was provided by the Islamic authorities managing the shrine. People in these nonelite groups thus regarded the festival primarily as a pilgrimage that honored Moses, not a public festival in honor of the Palestinian nation.

The anti-Zionist Jewish communists were the only Jewish groups that were involved with the festival. In the 1930s, they attempted to distribute Arabic-language pamphlets condemning British colonialism, wealthy Arab elite notables, and Zionists. The Jewish communists attempted to recruit Arab peasants and urban workers into a class-based movement, but it was difficult for most Arabs to dissociate European Jewish communists from Zionists.

Awad Halabi is an associate professor of history and religion at Wright State University, with a PhD in Near and Middle Eastern civilizations from the University of Toronto.