By Mikayla Mondragon

Gregory Alan Phipps, “Male Friendships and Betrayal in the Fiction of Graham Greene,” Texas Studies in Literature and Language 62.4 (2020): 415-36.

For readers who may not be familiar with Graham Greene (1904-91), could you give us a brief introduction?

Graham Greene is, in many respects, the consummate twentieth-century author. He lived through the major political, social, and cultural transformations that occurred across the century, and he engaged with these changes throughout his literary career. He is also an author who resists classification. You can see the influence of authors like Henry James, Joseph Conrad, and Ford Madox Ford in his writing, but he does not fit easily into the larger ambit of modernism. You can also see his experimentation with different genres (such as crime fiction) and literary style, but he tends to be selective in his usage. Finally, he is, in his own way, quite a spare and stark writer. He speaks in his autobiography about the importance of “compressing a story to the minimum length possible without ruining its effect,” and this approach is evident in his literature. He conveys a lot of emotion, conflict, and meaning through a limited use of words, and he rarely overloads his readers with description or explanation.

Which of Greene’s works is your favorite? Why?

The Power and the Glory. It is a novel about a specific subject in a particular setting—an anti-clerical purge in Mexico during the 1930s—but it is, above all, a brilliant portrayal of a hunted person entangled in questions of ethics, responsibility, and the meaning of life. It also offers a fascinating portrayal of a person’s conflicted relationship to the ideals of an institution in the absence of the material structures or hierarchies that normally sustain it.

Would you be willing to give us a list of his best novels?

I would probably say, The Power and the Glory, Brighton Rock, The Heart of the Matter, The Quiet American, and The End of the Affair.

What originally got you interested in Greene and his works?

He was one of the novelists I read and admired as I was growing up. I remember the first work of his I read was The Third Man, which, since it was written originally as the sketch of a screenplay, is actually a bit underdeveloped in its novel form. However, the edition I had also included another work that was adapted into a film called The Fallen Idol. This was an original short story entitled “The Basement Room,” which I thought (and still think) was wonderful. After reading these works, I proceeded to plough through many of his novels in the course of a year. I actually learned a lesson from this, though: if you really like an author, it is good to space out their works instead of reading them all at once. That way, you can keep discovering their literature at later points in your life.

Greene is interested in the subject of friendship, although he has an idiosyncratic take on it. Could you explore his philosophy of friendship in, say, Brighton Rock and The Heart of the Matter?

I am not sure if he has a particular philosophy. The male friendship riddled with threats of betrayal is a recurring theme across his literature, but it always seems to be an organic development within his narratives, as opposed to a perspective on life or society that he wants to convey through a novel. However, I think part of the reason for this impression is that Greene is a masterful writer of dialogue. Few authors are capable of expressing as much as he does through the ways his characters speak to each other. As a result, I rarely feel that Greene is trying to speak through his characters. Thus, his thematic interest in friendship and betrayal usually appears to be a reflection of his characters’ personalities and relationships, as opposed to an idea he wants to get across to his readers.

At one point, you suggest that characters in both of these works grow a stronger friendship as a result of betrayal. What message might this carry for Greene’s readers?

I think the point is that the moment of betrayal coincides with the moment that male characters truly become friends. It is almost as though the “great betrayal” has to occur in order for the friendship to exist. One might expect there to be a message about forgiveness woven into this dynamic, but in most instances, the so-called friends never see each other again once the betrayal happens (this is true, for instance, in The Heart of the Matter). However, Greene’s first published novel, The Man Within, does depict the fear and humiliation that haunts a character who has betrayed his friend, suggesting that, in Greene’s world, betrayal can be as traumatic for the person who commits it as it is for the victim. This idea also surfaces in The Power and the Glory, where the priest develops an almost friendly pity for the man who betrays him, recognizing that this act will weigh on the man for the rest of his life.

Both Brighton Rock and The Heart of the Matter are considered the gold standard of Catholic novels, yet Greene objected being seen as Catholic novelist. Why do you suppose that was?

I think many authors tend to resist such broad classifications. After all, various writers who have been identified as the leading figures in this or that famous literary movement pushed back against the idea that their works were an expression of the movement. Moreover, I think we can see throughout Greene’s career and life a distinction between a strong intellectual interest in Catholicism and a deep-seated Catholic faith. His faith seems to have moved in waves, and it remained precarious even at its high points. It may have been strongest when he was channeling it through his romantic life, such as during his courtship of his wife or his later relationship with Catherine Walston.

Do Catholic novels have a role in culture today?

Some of the specific issues with which Greene’s Catholic characters grapple might seem out of place today, but I believe many readers can connect imaginatively with the underlying conflicts he presents in his narratives. In The Heart of the Matter, the protagonist Henry Scobie lives as a good Catholic while barely paying his religion any mind. However, as his life spirals out of control and he sinks into subterfuge and corruption, he becomes more intensely aware of his faith. I think many readers can identify with the underlying conflict here. As long as we are following the conventional rules of a social institution or cultural doctrine, we can safely ignore them. It is as though superficial obedience relieves us of the need to think deeply about the issues. However, when we begin to clash against the rules, our complacent beliefs are shaken, and we are forced to examine our relationship to the larger paradigm.

Brighton Rock has been adapted on stage and even a film as recently as 2010. Why do you think Greene’s work is still relevant?

I think for the reasons I have already mentioned, but on a pragmatic level, also because his novels are on the short side. For example, The Heart of the Matter is longish by Greene’s standards, but it still only clocks in at about 270 pages. Why is this important? I think it matters because the art of the short novel is underappreciated, especially in contemporary society. There is an implicit idea that a masterpiece must be a long work, like Wallace’s Infinite Jest, for example. Greene shows that a short novel can be just as profound as a much longer one. I appreciate long novels since I like to immerse myself in their worlds for an extended period; but I also see the value of short novels, which demand less of a commitment and tend to be nicely portable, which makes a difference if you are reading in more than one place.

Greene clearly drew upon his biography for his tales of traumatic betrayal, including betrayals he himself committed. Did he wrestle with the ethical implications of so bleakly re-telling stories from his past and even present

Interestingly, Greene had a reputation during his lifetime as an intensely private person who disliked giving interviews, but then, his work is often heavily autobiographical. For example, The End of the Affair draws upon his affair with Catherine Walston. One of the reasons I was interested in revisiting his schooldays is that he regarded these years as the most miserable period in his life. In both Brighton Rock and The Heart of the Matter, you can see how he incorporates aspects of his schooldays into his literature—for example, in the latter, the relatively minor relationship between Wilson and Harris touches upon shared school experiences. Also, the first novel Greene wrote, an unpublished work entitled “Anthony Sant,” is set in a school and reproduces aspects of Greene’s traumatic experiences at his father’s boarding school. In this way, Greene started his literary career by recounting what was, for him, the worst experience of his life.

As a student, Greene experienced depression. How might his works be read differently in an era that talks more openly about mental health?

In retrospect, it seems evident that Greene was bipolar, but in his autobiography A Sort of Life, he uses the more tepid word “boredom” to refer to his bouts of severe depression. Then again, he also details how he took up Russian roulette to escape from this boredom, indicating that he realized the unusual depth and intensity of these low points. Norman Sherry’s three-volume biography of Greene only touches upon his bipolarity, preferring instead to treat his extreme and occasionally self-destructive behavior as symptomatic of the passions and demons that drove him. This approach downplays the role that mental illness played in his life and art, though I do think there is also the risk today of drawing too much upon this illness to explain the arc of his life. Biographers and critics would do well to treat such issues with balance.

If Greene were alive today, what would you ask him?

He mentions in his autobiography that working as a writer for a newspaper was, for him, the ideal training ground for a novelist, for some practical reasons (for instance, the hours he worked left him relatively free to focus on his literature), but also because this job enabled him to pick up “lessons valuable to his own craft.” I think I would ask him if this assessment still holds true today. For example, now there are so many creative writing programs in universities—are these places ideal environments for young authors, or can they be inhibiting? Also, I might ask him what he would have asked Henry James. I worked on James for many years, and I know Greene was a devoted admirer of his works, but they are so different—not just in terms of their literature, but frankly, in terms of their lifestyles. So I wonder how Greene understood the point of connection between them.

Greene’s works have had a rich legacy on screen. Could you please rank the film and television adaptations of his work for us?

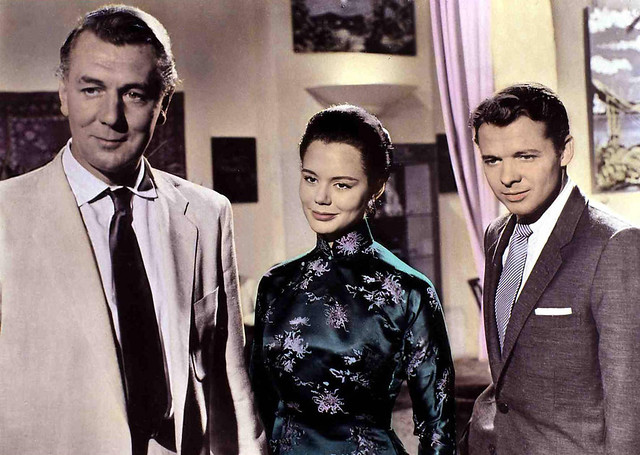

As a film, I think The Third Man is a great work. The original adaptation of Brighton Rock is very good, too.

What are you working on now?

I am working on a book that explores interconnections between Hegel’s philosophy and scientific narratives about the Big Bang.