By Erik Ching

The United States’s decision to revoke TPS (Temporary Protected Status) from some 200,000 Salvadorans living in the United States is morally repugnant. The gap between moral accountability and foreign policymaking is wide, even for a country like the United States, whose leaders’ idealistic rhetoric suggests otherwise. But if there was ever a country that owed another country something and one that should be held accountable to a moral standard, it is the United States in its historic relation with El Salvador.

The United States extended TPS to Salvadorans in 2001 after a series of devastating earthquakes. The Department of Homeland Security claims that the earthquake conditions that inspired TPS no longer apply, and thus Salvadorans can return home. Technically, that statement may be accurate, depending on how one chooses to define “earthquake conditions.” But the reality is that the situation in El Salvador has been deteriorating ever since, and the United States bears tremendous responsibility for creating those conditions. The United States has had a deep impact on El Salvador in pursuit of its own foreign policy needs going back to the 1970s, and its actions contributed not only to the historic flow of migrants out of El Salvador, but also to the current conditions of violence that prevail there.

The United States had an overwhelming presence in El Salvador in the 1980s. Under the Carter administration, but especially during the two terms of Reagan’s presidency, U.S. policy makers defined El Salvador as a foreign policy priority after the Sandinista victory in neighboring Nicaragua in 1979. Although the United States suspended military aid to El Salvador in December 1980, after four U.S. churchwomen were killed by governmental security forces, it reinstated aid in January 1981 in response to the guerrillas’ first “Final Offensive,” which more or less formally launched the Salvadoran civil war. Under the successive Reagan administrations, U.S. aid and the role of the United States increased steadily, particularly in 1983 and 1984 when it appeared that the Salvadoran government was on the verge of losing to the guerrillas. Overall, the United States provided on average $1 million per day of aid to the Salvadoran government throughout the 1980s, much of it in the form of military aid.

The justification for these policies was to prevent the supposedly Marxist guerrillas (the FMLN) from coming into power in El Salvador, as the FSLN had done in neighboring Nicaragua. Therein, U.S. policy makers tended to define the situation in El Salvador through the highly circumscribed and deeply flawed prism of the cold war, i.e. that the Salvadoran guerrillas lacked popular support and were a front for Soviet, Cuban, and/or Nicaraguan expansionist designs. One of the most definitive policy statements in this regard was Reagan’s address to the nation in May 1984 to appeal for support in providing more aid to El Salvador. In its framing of the situation in El Salvador and in standing by the Salvadoran government/military as steadfastly as it did, the United States prolonged the war and helped contribute to the brutal human rights record that the Salvadoran military accrued throughout the years.

With the benefit of hindsight and evidence, we now know definitively that the overwhelming majority of killing and human-rights violations being perpetrated in El Salvador were done by the Salvadoran military and/or paramilitary organizations with close military ties. What we also know now, but which we also knew at the time, is the large extent to which the United States either tacitly supported or willfully ignored the actions and activities of its allies on the ground in El Salvador, notably in events like the massacre of El Mozote in December 1981 (portrayed so clearly by the journalism of Mark Danner) and the assassination of the six Jesuits in November 1989, to list just two examples of countless others. Admittedly, at various times throughout the war, U.S. policy makers tried to get Salvadoran military leaders to amend their ways in the face of growing U.S. domestic opposition to the war, such as when Vice President Bush arrived in December 1983 and delivered a rather stern directive to the generals about cleaning up their act. But both sides recognized that the U.S. had planted its flag with the Salvadoran military and that it was unable and/or unwilling to do anything to jeopardize its cold-war inspired foreign policy initiatives in El Salvador. The killings and the torture went on, only beginning to abate after 1983.

In addition to the history of U.S. involvement during the civil war in the 1980s, the United States’s subsequent immigration policies have had adverse impacts on El Salvador, namely the deportations of Salvadorans in the 1990s and 2000s. Many scholars see these various kinds of deportation as giving rise to, or significantly contributing to, the explosion of gang membership and gang-related violence in El Salvador by entities such as MS-13 (Mara Salvatrucha) and Calle 18. Those gangs have their origins in the United States, as young migrants who fled from the violence of the 1980s became subsequently caught up in the desperation of life in the United States thereafter. Although some of the people that the United States deported back to El Salvador were gang members involved in criminal activity, the United States also sent back many young people, some of whom did not even speak Spanish and had no record of gang participation or criminality. When thrust into the alien environment of El Salvador, some of these young people could only find refuge within gangs, exacerbating the problem.

The overwhelming majority of the 200,000 Salvadorans currently residing in the United States on TPS are law-abiding people working diligently to make a better life for themselves, and therein contributing to the collective good. Throwing them back into El Salvador would be a human rights disaster. They will struggle to find their footing, they will be targeted for extortion, and their needs will be an added burden to a nation already short on employment. In 1969, some 100,000 Salvadoran peasants, living across the border in Honduras, were forced by the Honduran government to return to El Salvador en masse. This action helped trigger a subsequent war with Honduras, and the sudden return of this mass of Salvadorans also had a destabilizing effect on the nation’s society and economy, contributing to the downward spiral that led to the outbreak of civil war in 1980. I fear that the mass return of 200,000 Salvadorans from the United States in 2018 would have a similarly destabilizing effect, to say nothing of the consequences for many U.S. citizens who will be separated from their loved ones and family members.

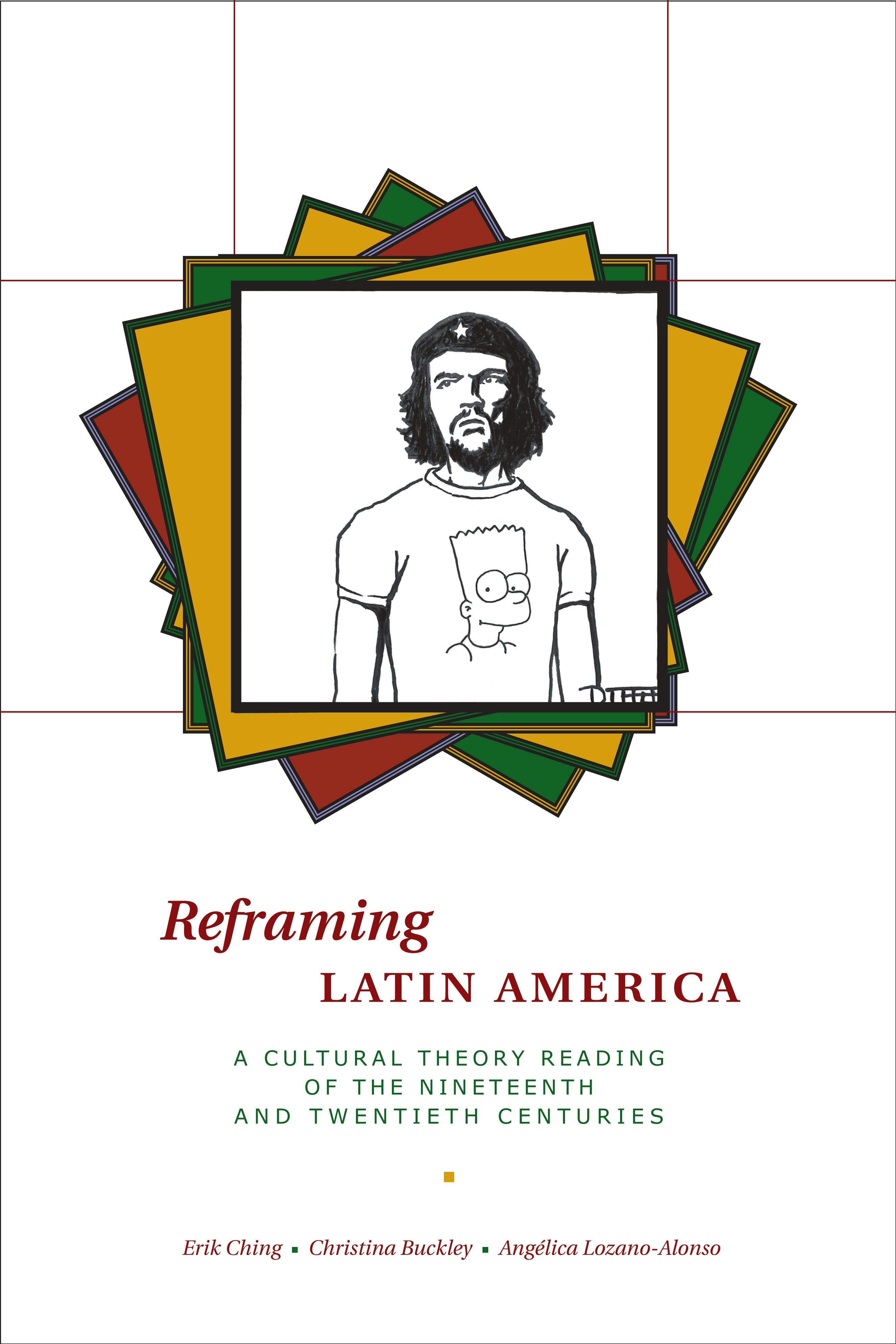

Erik Ching is a Professor of History at Furman University. He is co-author of Reframing Latin America: A Cultural Theory Reading of the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries (2007), editor of Broadcasting the Civil War in El Salvador: A Memoir of Guerrilla Radio (2010), and author of Stories of Civil War in El Salvador: A Battle over Memory (UNC Press, 2016).

Further reading: Erik Ching was quoted in a recent New York Times article with Gene Palumbo as lead author titled, “El Salvador Again Feels the Hand of Washington Shaping Its Fate.”